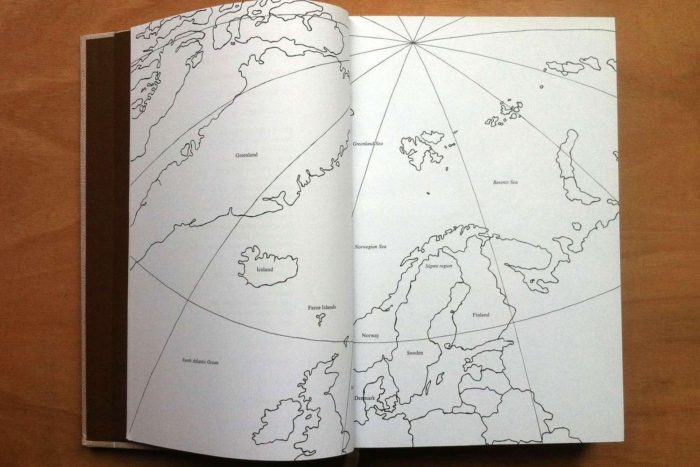

Next to the word ‘comprehensive’ in the dictionary there should be a picture of the cover of The Nordic Baking Book by Swedish chef and food historian, Magnus Nilsson. The meticulous head chef at Fäviken Magasinet in the remote west of Sweden, and author of 2015’s encyclopaedic ‘The Nordic Cookbook’, has left few baking stones unturned, from Iceland to the Faroe Islands, in pursuit of recipes for buns, breads and broths. That porridges and soups should appear in a baking recipe book is a major talking point in Nilsson’s distinctly casual approach to completism. It’s a point he takes time to explain, right from the start.

Nordic baking is, beyond doubt, a defining characteristic of how people relate to the nations in the region, or at least their ideas of what those countries are. Danish pastries, cinnamon buns, rye breads and all-butter biscuits flowed from Scandinavia into the bakeries and home kitchens of Europe and beyond a long time ago, yet the same can barely be said for Iceland, Finland and Denmark’s distant Faroe Islands. Nilsson has it covered and ‘The Nordic Baking Book’ is another stake in the ground for the chef as his nation, and neighbouring nation’s pre-eminent food archivists. There may be a grandmother sat, right now, on Gotland, wondering when he is going to arrive to collect her saffron braids recipe, but she appears to be the only one left out.

He is at pains, rightly to explain that, as a doughnut isn’t strictly baked, it falls into a grey area. But, leaving them out, alongside other fried recipes, would be pure folly. So, the boundaries are pleasingly stretched and things that go so well with cookies or after a meal, from fruit soups to jellified desserts, all find a home here. There’s nothing that wouldn’t please anyone already committed to spending time producing food that makes good memories.

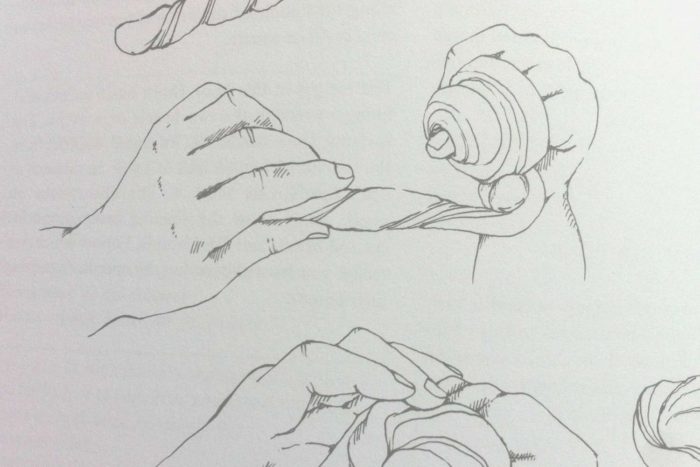

Line-drawn illustrations help to develop confidence, particularly the shaping of doughs, wrapping and knotting buns.

Over 450 recipes follow Nilsson from kitchen to kitchen, with the backing of family elders (the tips and preferences of his mother and memories of the tastes and aromas of his grandparent’s kitchen), and from worn notebook to faded recipe book, all in pursuit of traditional, workable home recipes that can transport the home baker, at all levels of experience, to the wilds of the Arctic Circle or a crowded Konditori at ‘fika’ time in Stockholm.

It contains generations’ worth of knowledge and a lifetime of recipes for everyone else. Nilsson starts at the beginning, with the birth of diverse grains and human ingenuity in unlocking the gift that nature has provided. From there, he provides the basics of many baking techniques, from the ground (kneading dough) up (tempering chocolate). Line-drawn illustrations help to develop confidence, particularly the shaping of doughs, wrapping and knotting buns, braiding breads and even a ‘cut-out’ template for a gingerbread house. Just short of buying the hard-to-find, traditional patterned rolling pins for flatbreads, Nilsson has done most of the work in advance. There are 29 useful chapters, excluding the index, including a page of recipe notes to finish (‘baking notes’ are at the start), the kind of addendum you’d expect written in pencil in the back of a battered family heirloom.

Nilsson makes a defining statement in early in the book that denies the importance of getting everything right, even following the recipes to the letter, rejecting the idea that baking is a science of ingredients. He is ready for other people’s mistakes and adjustments to create something new, potentially better. So, the pressure is off. It’s a book to enjoy, screw up and see what happens. If only we could all be so relaxed about what comes out of the oven. It’s hard to imagine buyers of such a beautiful and heavy book wanting anything other than perfection, exactly as Nilsson found it in that remote Lapland kitchen.

Some principles are as easy as the author claims them to be, or make themselves apparent in the reading of his authoritative, humorous, historic and nostalgic introductions to each chapter and many recipes. The way to make cinnamon buns, vanilla buns, vanilla suns and more are all made using the same dough, or any of a few, basic wheat bun doughs that Nilsson has dug out to serve all purposes. The reader chooses the one that sounds easiest or tastiest. It’s a helpful demystification of recipes that can seem daunting, especially in a world where the Kanelbulle is gaining near-canonised notoriety. Some recipes receive such casual instruction that the discretion of an experienced baker is needed for success, while others are written with such precision that the importance of not desecrating their tradition is implied.

Chefs have been seen to rage, defend their version of ‘right’ and Nilsson lets the mask slip just once, in the ‘Sweet pastries leavened with yeast’ section, pulling up sourdough bakers for their naturally-leavened attempts at those famous buns. They don’t work, so stop it, is a fairly curt message. Natural leavens are reserved, in abundance, for Nilsson’s bread section, where the absence of commercial yeasts, due to the wilds in which many breads are baked and the need for traditional grains to soften and mature, means that a gently bubbling pot of fermented flour and water really was, and remains, the favoured option.

Anyone looking for the ‘greatest hits’ of Nordic baking will find it in Nilsson’s book. Anyone looking to happily drown in the extended baking, wider culinary and heritage of the region can sink into recipes for all manner of pancakes, rusks, flatbreads, cordials, filled pasties, open-faced sandwiches, delicate Æbleskiver and rolled, sponge desserts, happily doing so with Nilsson’s caring and sharing voice in their heads and fleeting glimpses of far-away lands in the occasional, photographic interludes.

Putting ‘Nordic Baking’ to the test with just three, trademark Nordic recipes, some of the book’s key characteristics are put to the test.

Danish Rye Bread

L-R: The rough and ready, seedy test bake compared with the more composed, real deal.

“The reader may wish to substitute buttermilk for rye sourdough in this recipe”, which is easier said than done. Rye breads get 15 pages to themselves and the Danish ‘Rugbrød’ recipe reads as the one to go to for a definitive rye, the one seen beneath the equally decorative as they are delicious toppings of open sandwiches. It’s a five-day recipe of soaking and fermenting and easy to stray from, meaning first-time perfection may elude those without meticulous attention to Nilsson’s instruction. Yet, that troublesome substitution of buttermilk for rye sourdough is vague, rather than meticulous. In the test bake a rye bread emerged from the oven, healthily dense and strongly flavoured, yet the crunch of the un-scalded rye kernels from the first ferment gave the texture of millet bird feed, which was undeniably healthy, yet challenging to eat. The adjustments made weren’t right, perhaps the kernels, from an organic German health foods store, were of an unsuitable variety and the rise or dough temperature at the time of baking could have been better evaluated. Better luck next time.

Vanilla Buns

L-R: The satisfying results of the home made vanilla bun versus the ‘studio version’

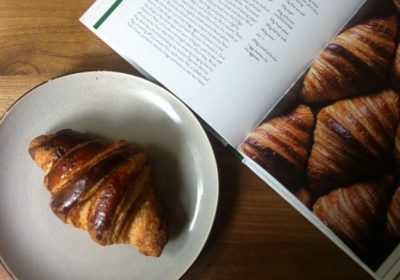

Three, sugary buns stare back from the page, daring you to make them. And all 27 of their brothers and sisters. One element of Nordic, particularly Scandinavian baking, is the economical use of ingredients, making relatively little go so far, with few bun or biscuit recipes falling short of 25 – 50 units at the conclusion. Vanilla buns start with a simple yeasted sweet, cardamom-infused dough, using 50g of fresh yeast in 750g of egg and sugar-enriched flour for an extra quick and airy rise, before receiving tablespoons of the book’s standard vanilla custard recipe. Encasing the custard can be tricky, but experienced dough-handlers need fear nothing. The buns are baked at 200°C for ten minutes, knocking 20°C off many, quick-bake Scandinavian bun recipes found in other books, making for a more balanced outcome and fewer nervy glances through the oven door. The outcome, once brushed with butter and dusted in sugar, is moreish and looks just like the book. The custard appears, not as gushing torrents, but as a largely disappeared, vanilla-flavoured moisture. It’s very welcome, but is it supposed to be that way?

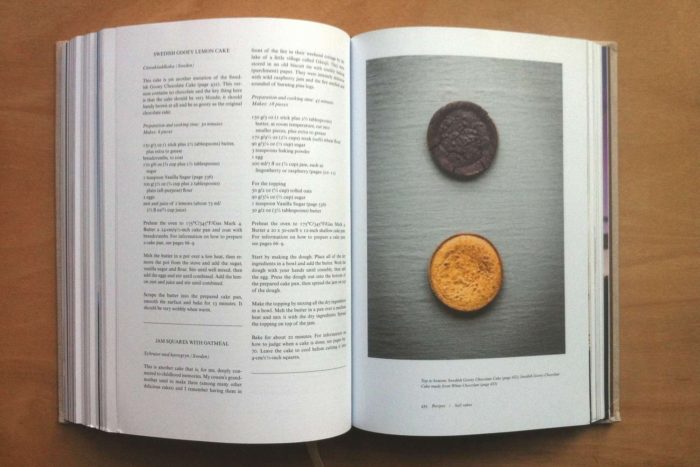

Kladdkaka

L-R: The test has fewer cracks, and perhaps a little less gooey than the model version, but as chocolatey as a cake gets.

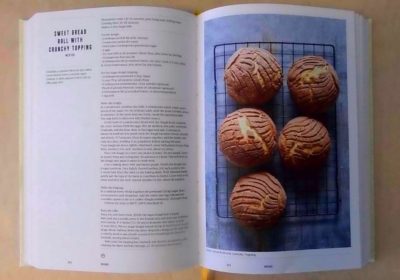

The cakes section of ‘Nordic Baking’ sets in a melancholy, for the fact one might not have enough baking weekends left to bake them all twice. Ideally three times. There are variations on the simple sponge, from an old Danish to the basic sponge largely accepted by bakers across Finland, Denmark, Norway and Sweden. A contemporary favourite, which Nilsson advises wouldn’t have been on Swedish tables prior to the 1970s, is Kladdkaka, or Swedish Gooey Chocolate Cake. It’s easy, on paper. Suspicion is that it was born of a baking disaster, with a poor, unleavened mix and an underbake producing what is, essentially, the first chocolate brownie. The limited ingredients, butter, sugar, a lesser amount of flour than in normal cake ratios and a heavy dose of cocoa, come with specifics from the author. To achieve the right level of gooeyness, it’s 13 minutes in the oven at 175°C, at least in Nilsson’s oven. It’s an imprecise science, with the rich chocolate cake coming from the test oven with a gooeyness that wasn’t headline grabbing, but a soft, uncakey consistency that was an approximation of Nilsson’s intention. It was a round Chocolate Brownie. Second time round, 11 minutes it is.

Read On…

Nordic Baking by Magnus Nilsson is published by Phaidon and is available now in hardback priced at £29.95 www.phaidon.com

Nordic Baking by Magnus Nilsson is published by Phaidon and is available now in hardback priced at £29.95 www.phaidon.com