In an age of extremes people are yearning for the simple life, in what appears to be ever growing numbers. Barely a day goes by without someone, usually on social media, screaming out for quiet walk in the park, a ‘normal’ cup of coffee and a loaf without lacy crust scoring and huge, butter-freeing holes in the crumb. Yes, it seems that the basics are appearing more attractive, the weirder and more wonderful the options available to us get.

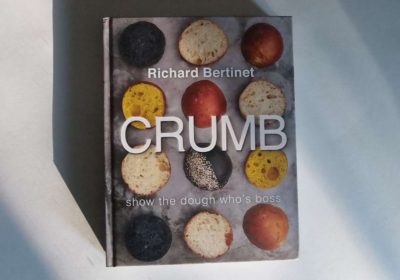

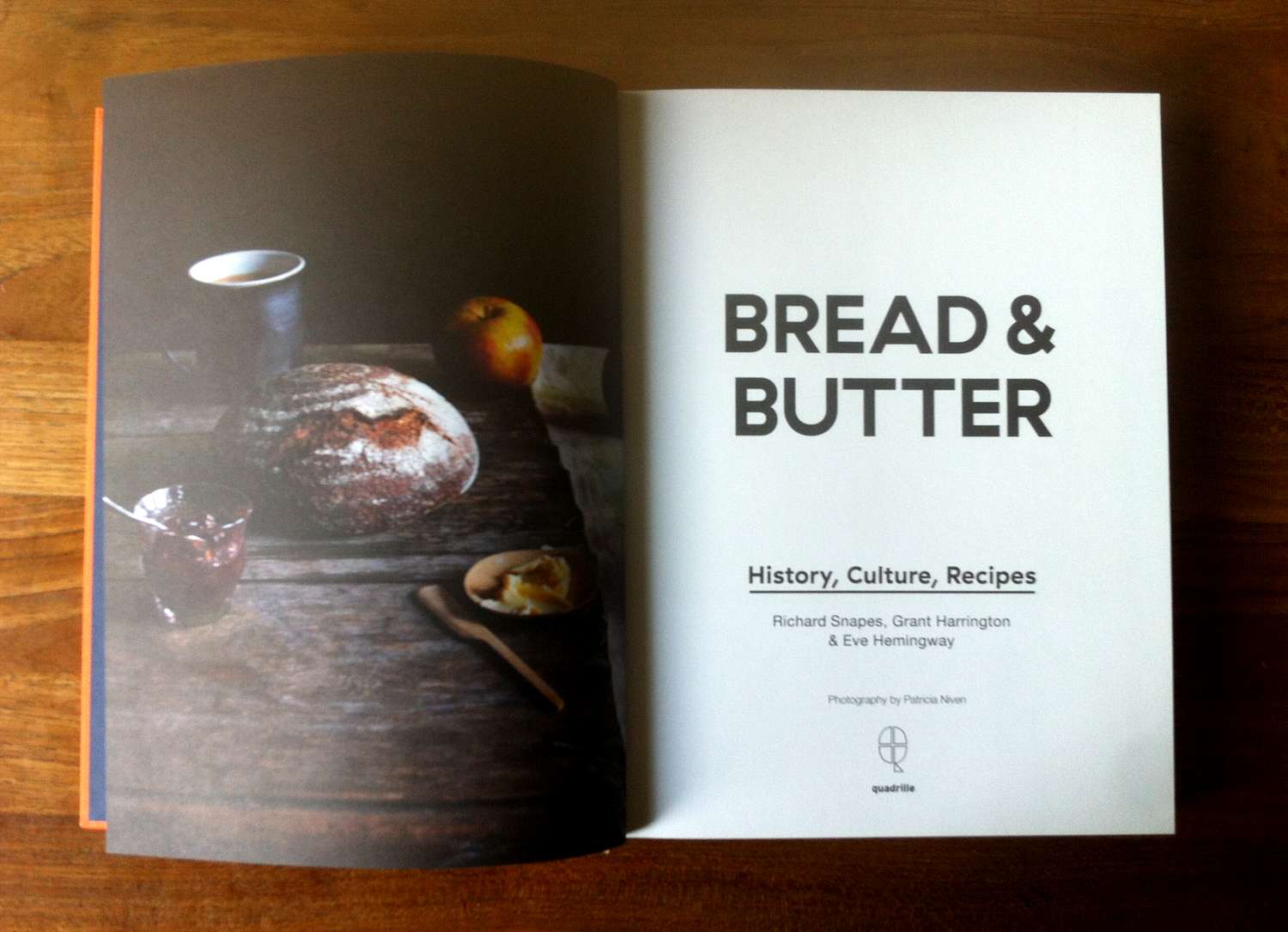

So, here we are with a book titled ‘Bread and Butter’. Why has it taken so long for someone to write it, given that the combination has been with us for as long as people beneath the oldest graves in any cemetery can remember? The combination of baker, Richard Snapes of London-based bakery, The Snapery, butter producer, Grant Harrington and food writer, Eve Hemingway makes for an eminently trustworthy, evidently enthusiastic and presumably well-qualified trio to guide the reader through the origins of the pairing and, once the science and history of their existence are digested, learn a bit more about making both.

255 solidly-designed pages bound in striking orange hardback, complete with photography as beautiful as entirely necessary in a hyper visual age, are the fruits of Snapes’, Harrington’s and Hemingway’s labours and it’s a real journey of discovery. The simplicity of the title belies the varying complexities, often daunting, of that which lies within.

Snapes brings classics from the bakery forth for the accomplished home baker to get to grips with. To say that it’s best for baking combatants to have some experience, and no dimmed lust for taking on some ingredient/instruction heavy tasks may be an understatement. The stages on the way to a sourdough loaf, perhaps The Snapery’s own Field Loaf, are exhaustive and, when set alongside the relatively simple and successful instructions of books published by other, respected bakers and bakeries, could present more hurdles than encouragement to a new baker feeling there’s light at the end of the long-fermented dough tunnel.

There is a wide range of breads to try, from brioche to flatbreads, so plenty to go at if one seems less adventurous than the other. Bakers flying the flag for simplicity and demystifying the process may need a bag to breathe deeply into or wish to move straight on to other sections. Bakers relishing heavy detail and blessed with ample time, step right this way.

The book goes on to explore what butter really can do, with delicious looking recipes for Butter Chicken Curry and, brilliantly odd, a Brown Butter Danish Daal recipe

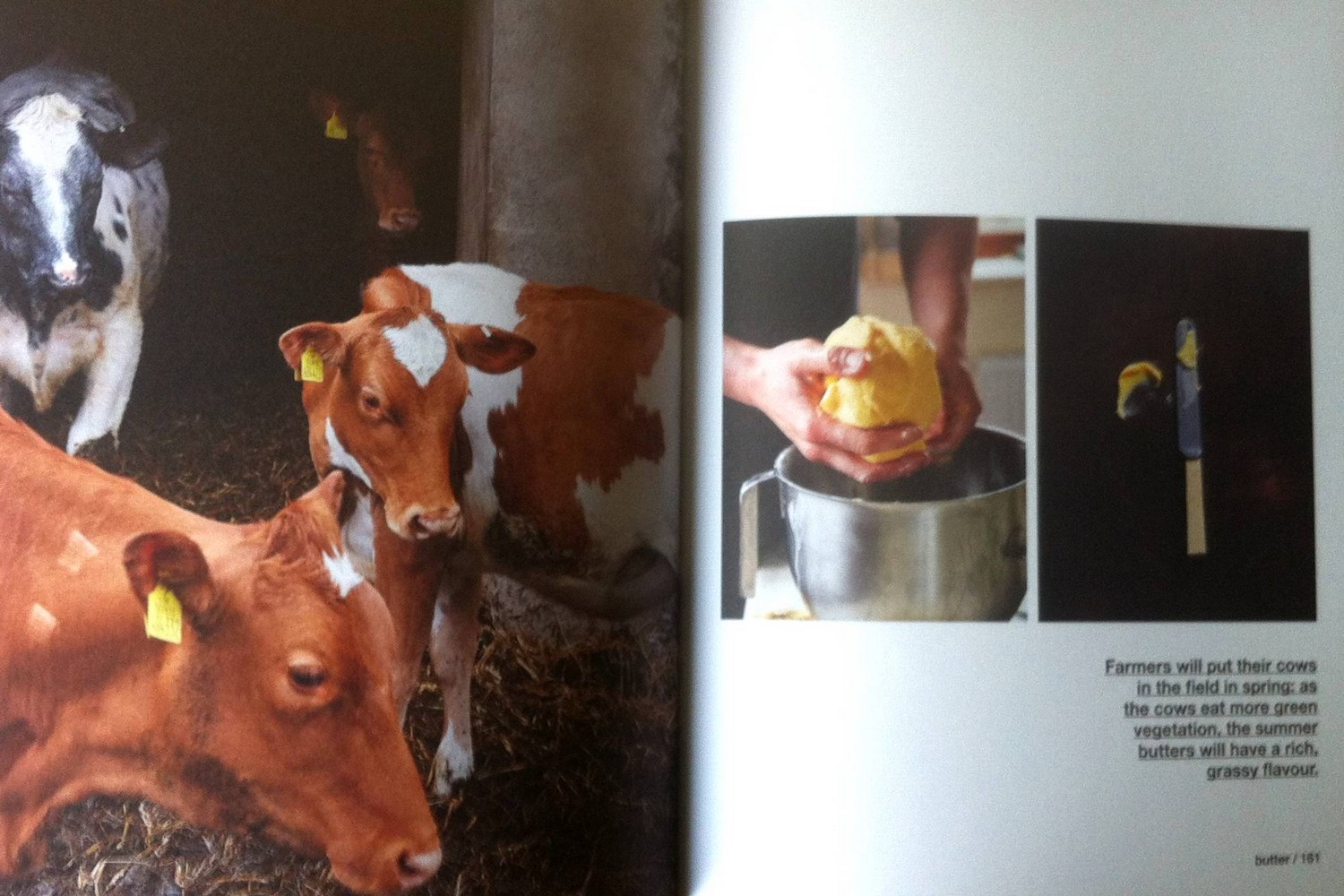

Nobody makes butter themselves, do they? Perhaps in the lead to kick start a new trend of garden shed and kitchen-sink butter producers, Harrington’s ‘Ampersand’ dairy products line is no small point of inspiration. Overlooked and taken for granted, what Harrington is talking about vitally is ‘cultured butter’, turning heads from the mass-produced blocks to something of an altogether different nature, made complex by the starter of yoghurt or soured cream. The book goes on to explore what butter really can do, with delicious looking recipes for Butter Chicken Curry and, brilliantly odd, a Brown Butter Danish Daal recipe. How a daal emanates from Denmark is easily explained by former resident, Harrington in just one of the book’s captivating encounters with the yellow stuff.

What Hemingway’s gift brings to the table is a vision for bread and butter’s union, as well as exhaustive, historical and globally-aware notes on the development of all elements that have brought, and keep bread and butter at the centre of everyone’s tables. Beyond the basics, a range of recipes that combine bread and butter and an ingenious ‘leftovers’ section – a title which may do the chef-standard recipes an injustice – are evidence of a cogent and worthwhile collaboration. Making Tibetan Butter Tea will be eminently easier than brewing beer from your remaining bread, but this is a book for retired atomic physicists with a surfeit of time, patience and brain space as well as weekend hobbyists with an afternoon to kill. The best advice is: be careful which project you take on and plan it well.

Putting the book to a test that really only skimmed the surface – a journey into butter making, some Snapery signatures and the creative consumption of lingering leftovers – offered equally intense, satisfying and head-scratching results.

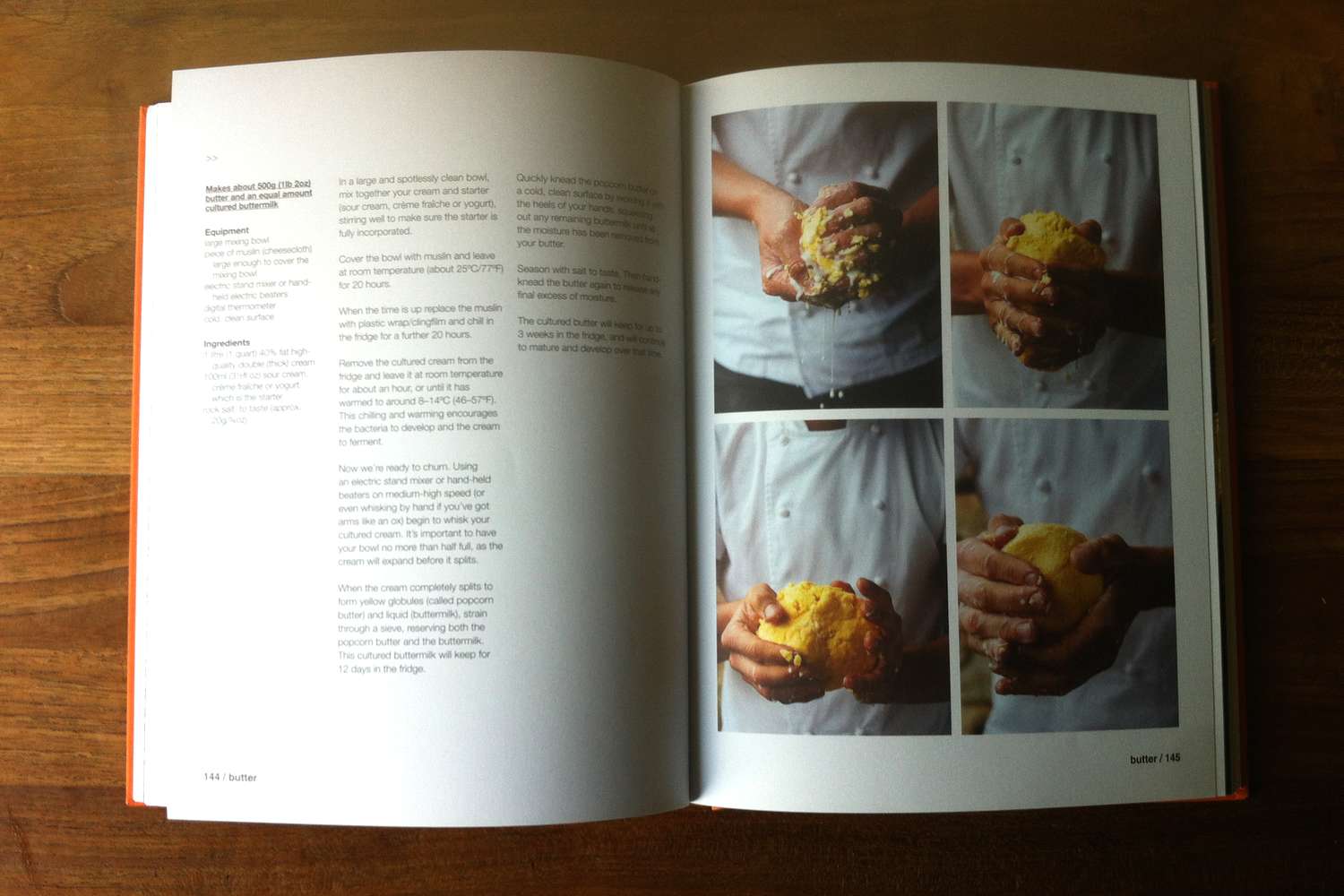

Cultured Butter and Buttermilk

L-R: A total pleasure by virtue of its complete rate of satisfaction. Homemade, cultured butter!

Why haven’t you tried this before? It’ll surely be a question playing on the lips of anyone who encounters Bread & Butter’s clear and well-illustrated process for cultured butter and, inevitably, its useful bi-product, buttermilk. The first satisfying point is that, for busy explorers, the making of cultured butter takes two days and the work required is next to nothing, yet the result is a knock-out for a first timer. After leaving a mixture of double cream, soured cream or yoghurt (the necessary bacteria source) to develop at room temperature, in the fridge and then back to warmth, it’s whisked. Just as tears of defeat are forming, convinced that all that’s been created is a slightly sour whipped cream, it miraculously and very quickly splits to create the butter ‘popcorn’ and buttermilk. Gathering the globules of butter and squeezing out the remaining moisture is surprisingly tough, it just keeps coming (and, to be honest, remained present in this debut attempt), but the process is as satisfying and simple as any you can have on your own in your kitchen.

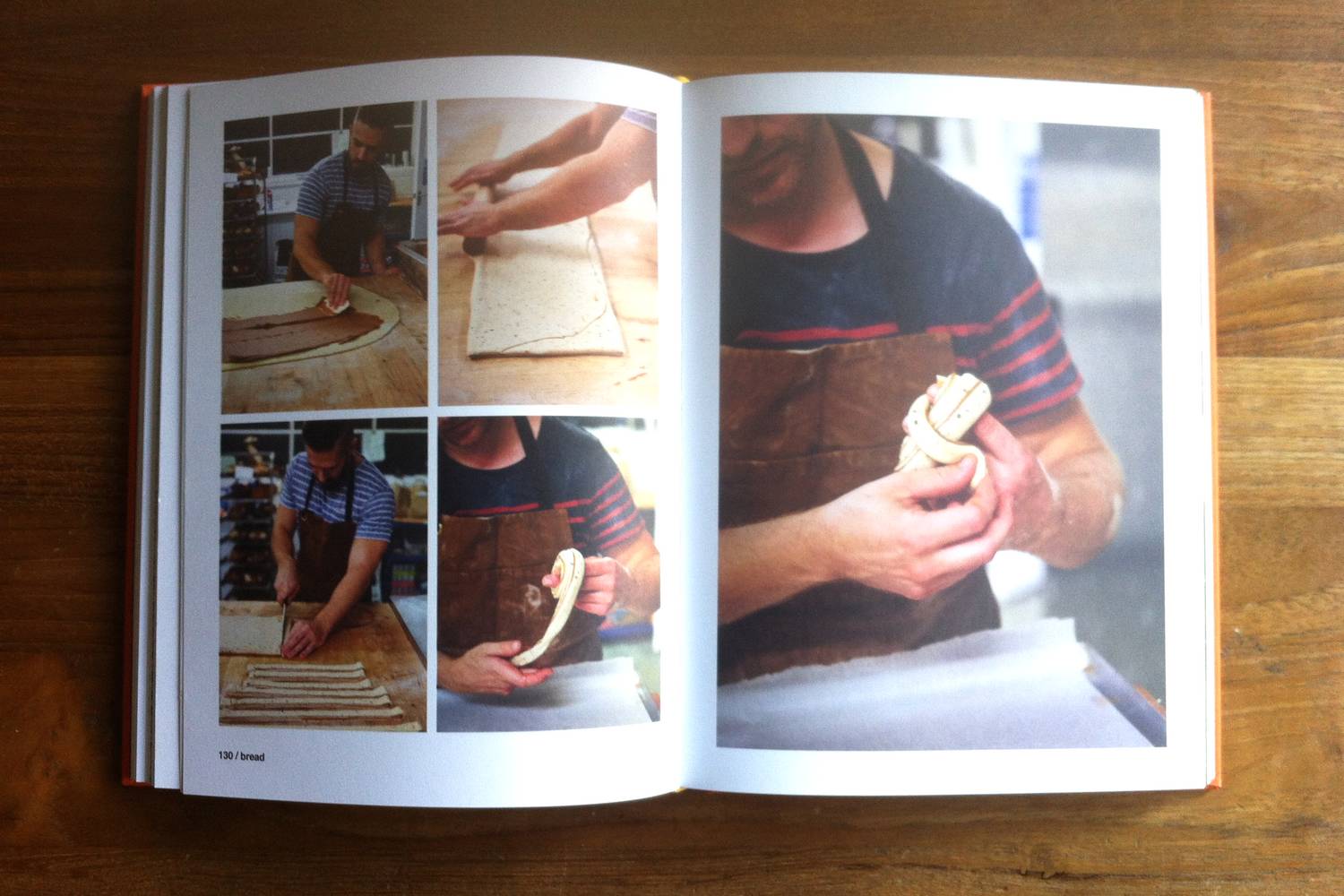

Knäckebröd

L-R: The tooth-breaking cracker, bearing the scars of the oven, with its superior cousin beside it.

Not all doughs are created equal and nor are all parchment papers. Yet, in trying to create The Snapery’s take on a Scandinavian classic, the dough and the parchment paper found each other irresistible. Here’s a recipe that’s ominous in the addition of a sourdough starter without knowing really what it’s meant to achieve. A short resting time of just 30 – 40 minutes for a dark rye dough infused with sugar, caraway seeds and rapeseed oil leads to the rolling out into the form of a thin cracker. Rolling a neither too-stiff nor too-soft dough out between two pieces of parchment paper isn’t easy to start with. Especially to a thickness of 1mm. The dough went thin to transparency when it got near, it bunched up at one end, there was too much of it… it was a recipe for stress if not total failure. Then, the paper wouldn’t come away. The outcome was far fewer bakeable crackers than the guidance stated, all of which tasted great, but were too thick and, sadly, caught incredibly easily in the oven. Perhaps one for more learned scholars in the realms of Knäckebröd production and more experimentation with Snapes’ guide as the pushing off point.

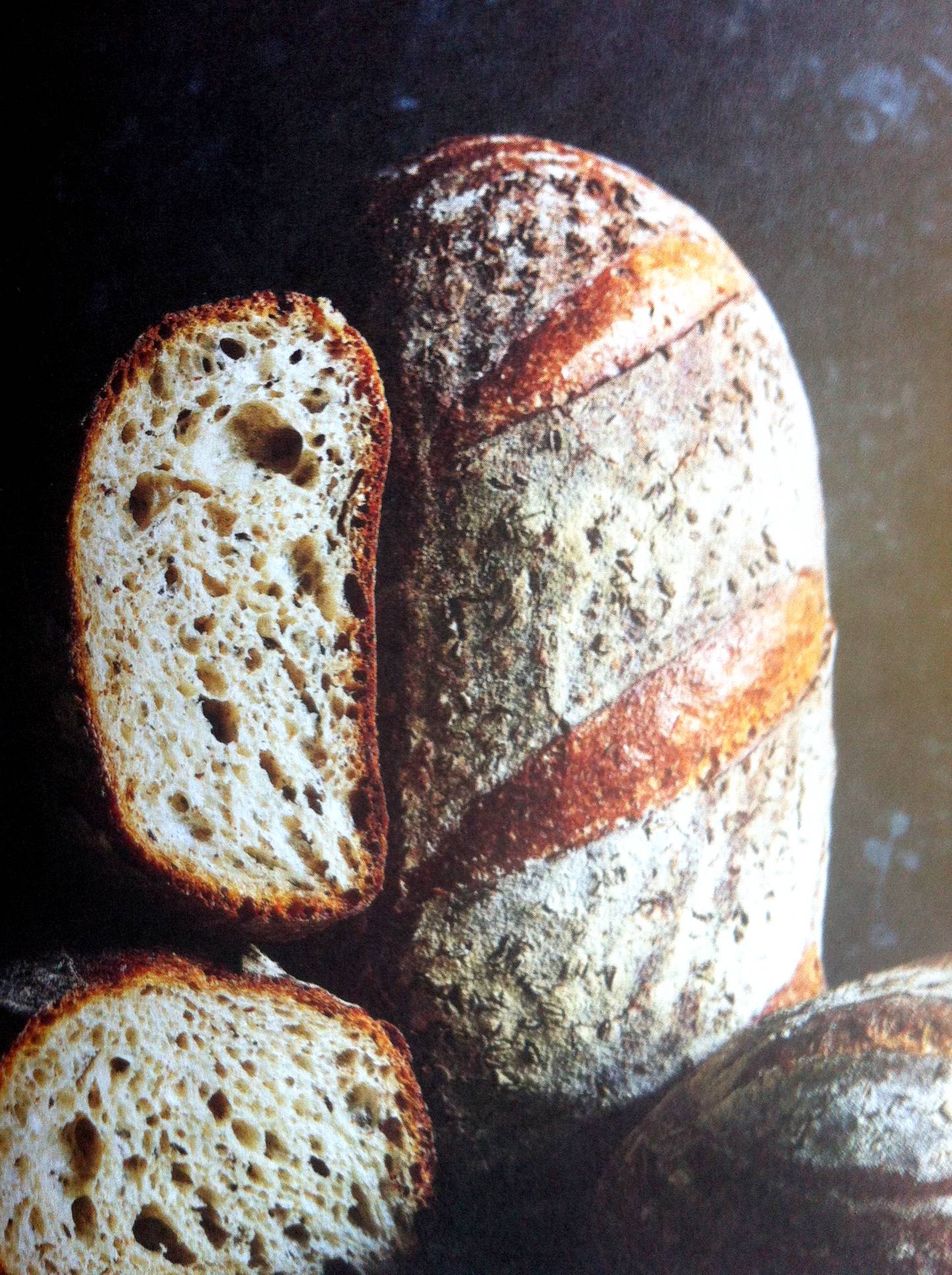

The New York Deli Loaf

L-R: A pretty standard white sourdough loaf compared with something that looks kind of similar.

How hard is it to make a sourdough loaf? Surprisingly easy in some circumstances, maddeningly inconsistent in others. From Snapes’ recipe for a white sourdough loaf, made a native of The Big Apple with the addition of those aniseedy caraway seeds, came two wildly different loaves. Using the ‘dutch oven’ process, out came an oddly dense, flat and unspectacular loaf. Going at the second dough with a steam bath and restricting the headroom in the oven with a roasting tray on the shelf above the loaf, a golden brown, blistered and evenly-risen bloomer came out. Same starter, same bulk rise and yet two breads that appeared completely unrelated. Criticism that can’t be levelled at Snapes’ chemistry in such circumstances, although what can reasonably be challenged are the quantities in the recipe and the complexity spread across multiple pages in attaining what is essentially a decent, solid white loaf. It seems impossible get ‘two large loaves’ from what’s put in, with both post-shaping loaves looking lost in their bannetons, even after a lengthy period in the fridge pre-baking, but that’s also a matter of personal perception and, maybe, how big your bannetons/hands are.

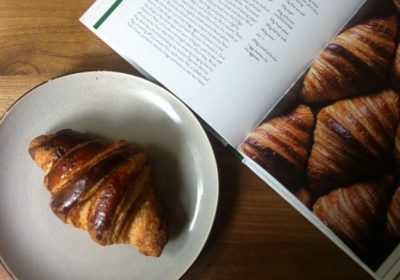

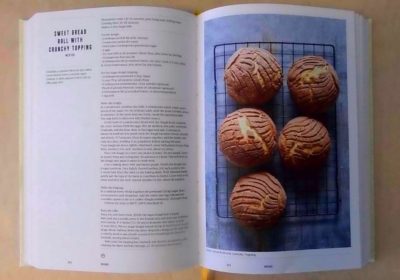

Kannelbullar

L-R: The shiny, buttery and sweet finished test Cinammon Bun versus the tightly-wound model example.

A classic of our age and times past, the Scandinavian cinnamon bun, a recipe that offers deeply satisfying results with minimal effort. Whether Magnus Nilsson’s traditional enriched dough or Swedish Cakes and Cookies easy step-by-step method ratified by generations of home bakers, it should be an easily surmountable hill on the way to the best tasting breakfast or coffee break of the week. In Bread & Butter it becomes a mountain, with ingredients including both apricot jam and marmalade, plus rolling into different balls, repeated proving and freezer resting time. On first read it seems too much hassle. On closer inspection, admittedly, it’s not that much of a Mensa test, yet if Bread & Butter’s ‘going above and beyond’ attitude isn’t compatible with a home baker’s more modest ambitions then the relationship is doomed. The twist in this particular tale is that, despite the dough being just on the wrong side of pliable to manage the neat knots in the shaping guidance, these buns are remarkable and freeze/refresh brilliantly if eating all 15 of them is too much. Almost like a cinnamon-flavoured bread and butter pudding consistency, the butter, sugar and spice mix soaks the soft, just-baked dough in ways that will draw random, indecent sounds from anyone biting into them. The privilege of comparing Snapes’ fussiness to the alternative of traditional, Scandinavian functionality is all ours.

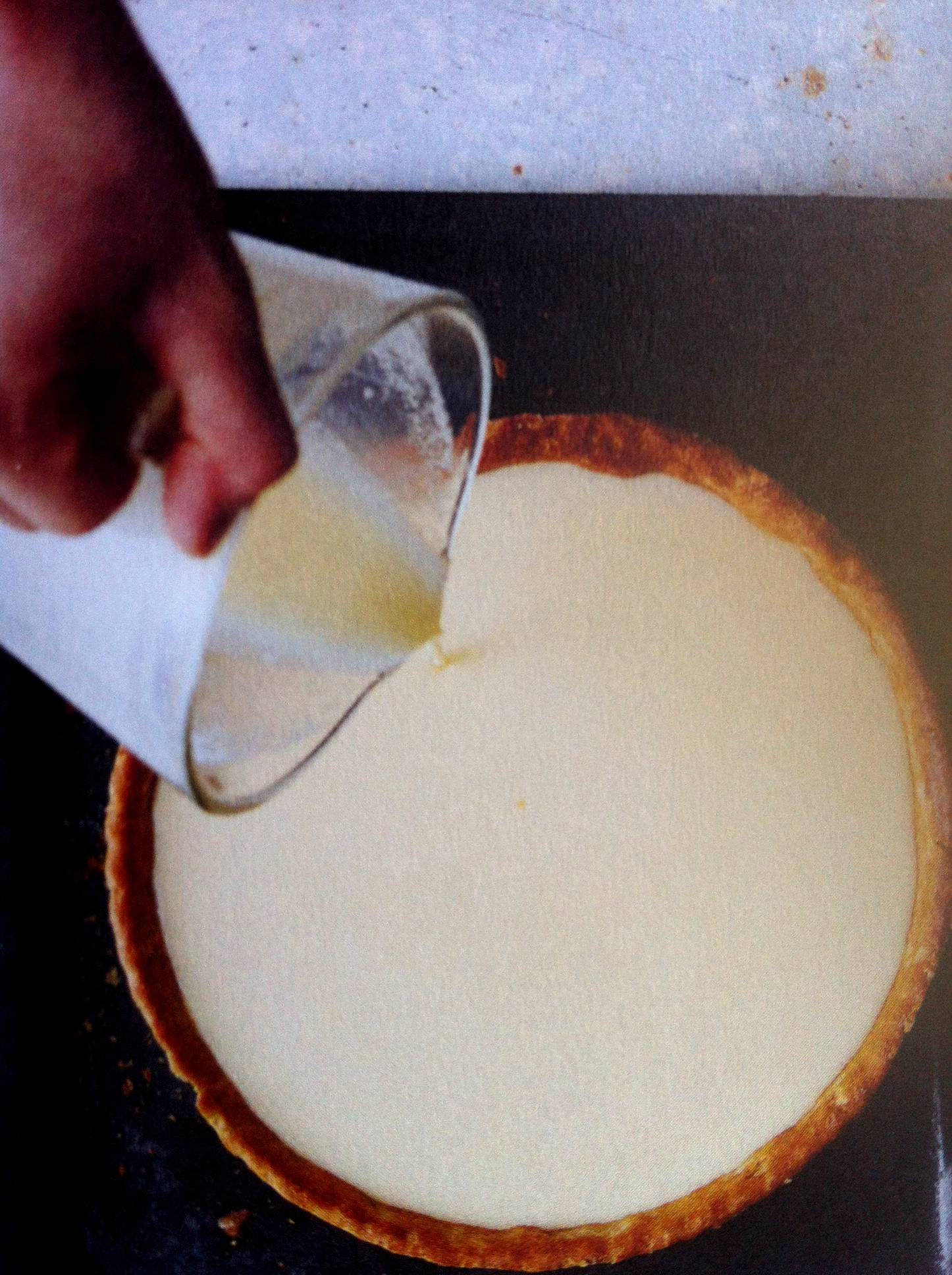

Buttermilk Tart

L – R: The finished tart, complete with browned sugar on top. The book doesn’t illustrate the final stage.

Surviving the intensity of 245 pages to get to page 246 deserves some reward and the Buttermilk Tart appears to be just recompense if it were needed, as well as a fantastic test of what the homemade buttermilk can achieve. Making the pastry for the tart should have been simple and, from the start that appeared to be the case, with a loose semi-dry mix of flour, salt, sugar and (home-churned) butter going all breadcrumby in a food processor before egg white and water take it to the next step. It’s the right consistency to roll after refrigeration, so far so good, yet the blind bake may require baking breeze blocks, rather than beans, to inhibit the magic, expanding, cakey quality of the end result. What happened next only brought sogginess to the sorry-ish base. The zest and juice of a lemon, of course relative to the size of the lemon itself, punched any other flavours into an incontestable knock-out result, rendering the poor buttermilk a mere carrier for the citrus and the lollipop sweetness of 150g of sugar. That seems a missed opportunity. With the aid of the seven egg yolks and cornflour, the filling set as described, yet beneath a caramelised skin, further ‘brûléed’ under the grill with a scattering of caster sugar, the consistency was more wet, sweet, lemony egg-custard than a happy, keenly anticipated balance of the ingredients and effort that went into making it. Was it right? Was it a mistake? Who knows? It’s the bittersweet taste of undimmed baking ambition and lingering doubt.

Read On…

Bread & Butter by Richard Snapes, Grant Harrington and Eve Hemingway is published by Quadrille and is available now in hardback priced at £29.95 www.hardiegrant.com

Bread & Butter by Richard Snapes, Grant Harrington and Eve Hemingway is published by Quadrille and is available now in hardback priced at £29.95 www.hardiegrant.com